This post is a review of the Spartan Mosquito Pro Tech, a tube containing sugar, yeast, and boric acid that you fill with warm water and position around the perimeter of your property. The cap has a series of small holes (approximately 5/32″) that are supposed to allow the release of carbon dioxide (a mosquito attractant) and also accommodate the passage of mosquitoes. Per the company, the tubes allow you to “take back your outdoor space”.

Here is how a mosquito is supposed to be killed by a Spartan Mosquito Pro Tech:

- mosquito is attracted to the tube by CO2

- mosquito lands on the tube

- mosquito crawls around until it finds a hole in the cap

- mosquito squeezes though a hole

- mosquito walks down side of tube toward liquid

- mosquito ingests some of the liquid (which contains boric acid)

- mosquito walks back up walls of tube

- mosquito finds hole

- mosquito squeezes through hole

- mosquito flies away

- mosquito dies from boric acid ingested in step 6

Do they work?

No. I tested four tubes in my yard in Pennsylvania and there was no noticeable drop in the numbers of mosquitoes biting me. I never observed a mosquito near any of the tubes. I looked inside all of the tubes and never found a mosquito.

In addition to the above observations I used a home security camera to spy on one tube continuously for over a week, to see whether mosquitoes might be showing up when I’m not watching (e.g., at night). Here are the details of what I did (photographs of setup are below). The camera didn’t record the presence of a single mosquito. I concluded that the Spartan Mosquito Pro Tech is not capable of killing mosquitoes outdoors because mosquitoes are not even attracted to it. I.e., it fails at step 1, above.

Why doesn’t the Pro Tech attract mosquitoes?

Based on what the inventors have said publicly, the carbon dioxide produced by the yeast is supposed to fool mosquitoes into believing there’s an animal inside the tube. I think this scenario is implausible. Although it is certainly true that mosquitoes use carbon dioxide to find hosts, I doubt the yeast is making enough carbon dioxide to attract mosquitos. And certainly not for an entire month. I think it is unlikely that Spartan Mosquito even believes this actually happens. I.e., the company has decided to claim the tubes attract mosquitoes because saying that is likely to convince some consumers it actually happens.

How did the Pro Tech get an EPA registration?

The EPA is famously strict about approving pesticide registrations, so it is unclear how this product managed to slip through. One explanation might be that Spartan Mosquito supplied data from experiments using caged mosquitoes. In this scenario, a known number of mosquitoes would be released inside a cage that contained a Spartan Mosquito Pro Tech, and their survival over time would be compared to that inside a control cage. There are some obvious problems with testing attractive toxic sugar baits (ATSBs) in cages. The most glaring is that there are no alternative sugar or water sources for mosquitoes and thus the test doesn’t measure, at all, how attractive the device might be in the real world (consumers’ yards).

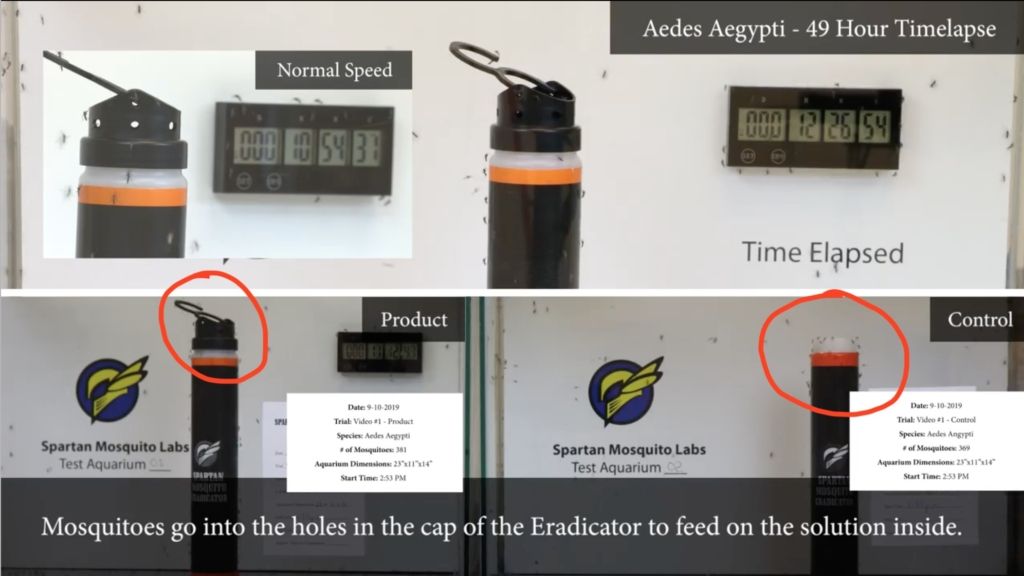

Another major problem is that Spartan Mosquito seems to set up experiments in a way that biases the outcomes. This can be illustrated by evaluating an experiment involving the Spartan Mosquito Eradicator they posted about on Facebook:

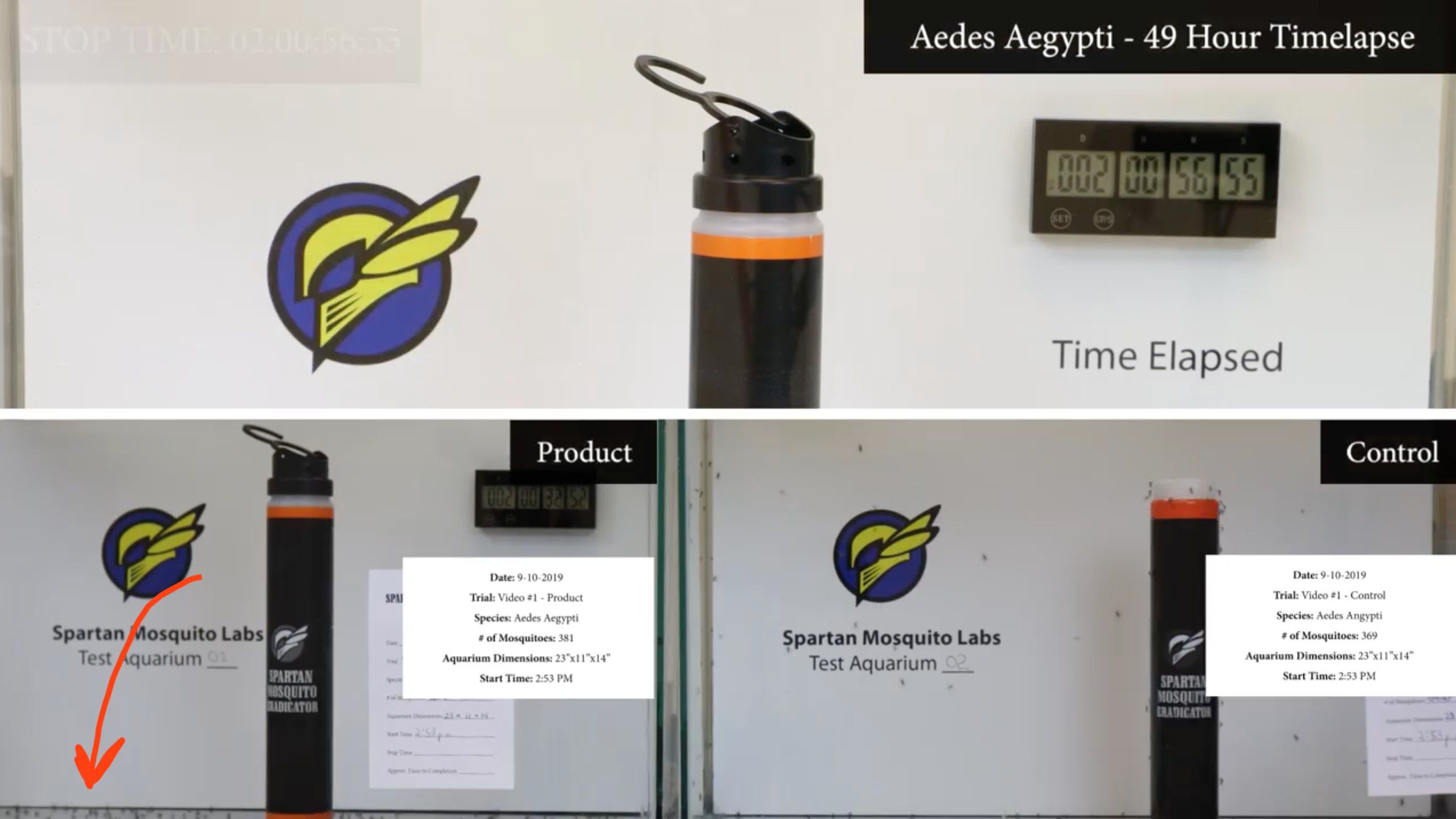

On the bottom left of the video there’s a view of the “Product” treatment — this tube is presumably filled with sugar, yeast, water, and salt (the listed active ingredient). The tube on the right shows the “Control” treatment, presumably filled with only sugar, yeast, and water (but no salt). However, the Eradicator in the “Control” cage doesn’t have a cap. The absence of a cap means that mosquitoes in search of water and sugar can easily get both simply by crawling into the tube. I.e., the experiment was designed in a way that ensures mosquitoes in the “Control” tank lived longer than those in the “Product” tank.

But because we have no idea how Spartan Mosquito set up the “control” tubes, the bias could be even more dramatic. If, for example, the control tubes had only water or were empty, they would not be producing any carbon dioxide at all. In contrast, the experimental tubes would be generating enough of the gas to potentially asphyxiate the mosquitoes inside the aquariums. Carbon dioxide is heavier than air so you’d expect higher mortality in cages with the “product” treatment; but the deaths would have nothing to do with the active ingredient (salt).

The video also reveals another strategy of Spartan Mosquito, that of implying that all 378 mosquitoes that died in the “Product” cage died because they entered the tube, ingested some fluid, then died. You can see part of this pile of dead mosquitoes at the bottom of the screen grab below (left).

There’s zero evidence in the video that any of those mosquitoes ingested the fluid inside the tube. All that’s presented in the video is a compilation of 3 or 4 clips showing individual mosquitoes entering or exiting the tubes. The screen grab below shows one of these instances along with the suggestive phrase, “Mosquitoes enter Spartan Mosquito Eradicators to feed on the solution inside.”

What’s important to notice here is that the company did not include a compilation of hundreds of clips showing mosquitoes going into the tube. If Spartan Mosquito had these clips I’m positive they would have used them. Plus the video doesn’t show a single mosquito exiting with a distended abdomen, which would be evidence that a mosquito had ingested fluid. My conclusion is that all the mosquitoes piled up on the bottom of the “Product” cage died from some other cause. The most likely explanations are that they died of dehydration or CO2 poisoning. Regardless, it certainly had nothing to do with mosquitoes going inside and drinking saltwater, because scientists have showed that the saltwater in Spartan Mosquito Eradicators is not lethal to mosquitoes.

The experiment I’ve critiqued above concerns a “minimum risk” pesticide, of course, and I acknowledge that Spartan Mosquito may not have needed to be particularly careful in how it set up and analyzed experiments (many states don’t even require proof that such devices work). However, it seems possible that the company adopted some of the same strategies when designing experiments for the Spartan Mosquito Pro Tech. And it seems possible the company might represent the outcomes to the EPA in the same way, persuading regulators that the deaths in the “Product” treatment were from mosquitoes going inside the tubes and then drinking the toxic fluid, when in reality there’s no real evidence of that happening.

The backstory

Given all of the above, I was not surprised to eventually discover that the EPA registration decision was not just based on efficacy data. Instead, Spartan Mosquito apparently convinced the EPA that the device should be fast-tracked. I first learned of this from a radio segment featuring Jeremy Hirsch (the inventor, founder, and current chairman of the board). During the interview the host said, “Hirsch is attempting to get an early green-light because mosquitoes are so dangerous”.

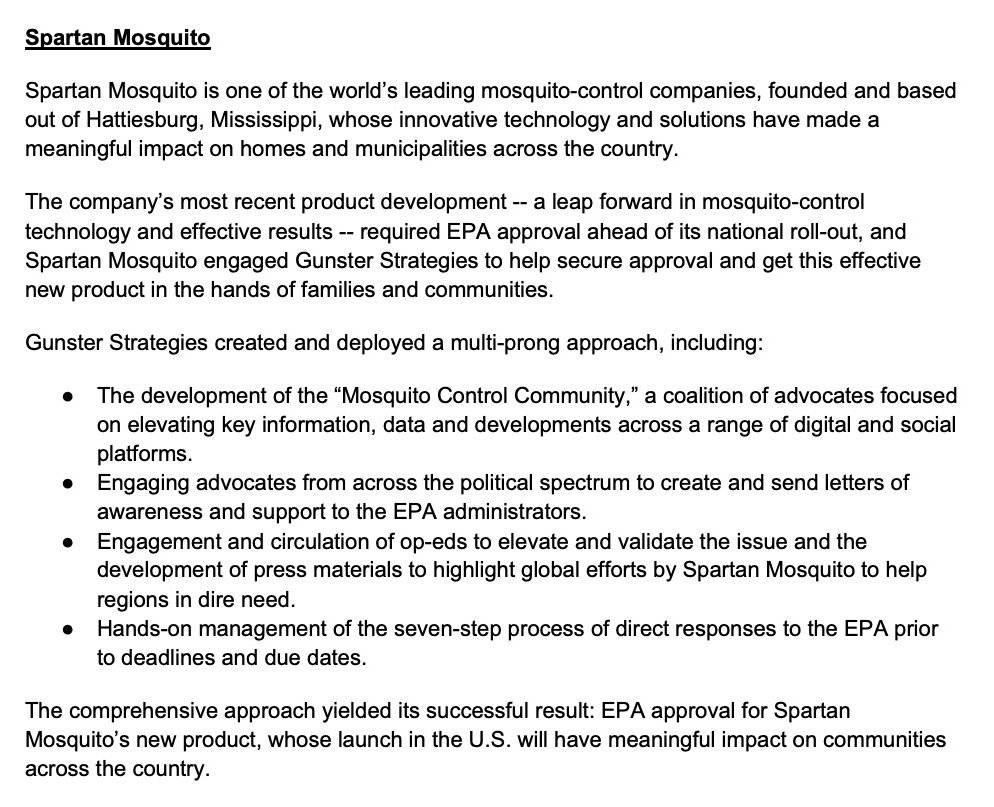

How, exactly, does one persuade the EPA that a pesticide should be rushed through the registration process? It turns out that Spartan Mosquito hired a lobbying firm (Gunster Strategies Worldwide) to get this done. Below is a document (now deleted) that I found posted on Gunster Strategies’ website. The scheme is spelled out in astonishing detail:

In regard to the op-eds mentioned in the document, it appears that an influential health official in Togo (Dr. Dr. Atcha-Oubou Tinah) was one of the writers, though it came in the form of a press release. I’m not convinced, however, that he actually wrote it.

I’m still trying to figure out who the firm payed to write letters to EPA officials. I would also like to know which administrators at the EPA were targeted.

Although not mentioned in the strategy document, Spartan Mosquito and one of its founders (Jeremy Hirsch) gave approximately $10,000 to the Cindy Hyde-Smith, the senator who chairs the committee with EPA oversight. I don’t think they donated to any other senator. It would be interesting to know whether Senator Hyde-Smith was one of the persons who called or wrote EPA officials about the Pro Tech.

I’m not sure how it fits into categories listed above, but it’s possible that two companies (see below) were created for the sole purpose of influencing the Pro Tech’s registration process at the EPA. Both companies claimed to be non-profits, but they were both singularly interested in promoting Spartan Mosquito. So my guess is they were involved in the scheme.

1. Innovative Mosquito Control, Inc

Innovative Mosquito Control (INMOCO) purports to be a public benefit corporation devoted to fighting malaria in Africa. As part of this effort it claims to have partnered with Spartan Mosquito to promote/supply the company’s tubes to the region. Its CEO and President is Omar Arouna (2nd from left in photograph below), a lobbyist based in D.C. who typically charges $1,500/hr for consulting and social media campaigns. There’s no further information on who works at the company or whether it even has employees. Contributing to the lack of information is that fact that the business was set up in Delaware, a state popular among companies that want to keep the true owner secret. And the company’s website was housed on a server in the U.S. Virgin Islands, also famous for companies that want to obscure their operations. It all seems needlessly secretive for a company that is ostensibly fighting malaria. But here’s the interesting part: Mr. Arouna has worked with Gunster Strategies on several occasions. And as a minor fact, both INMOCO and Gunster Strategies use Wix for websites. So I’m guessing that INMOCO was dreamed up by Gunster, which also hired the frontman. (UPDATE: Gunster has officially hired Arouna.)

What’s also interesting is that soon after the Pro Tech got its registration from the EPA, INMOCO’s website was taken down and its Facebook page has had no further posts. And Mr Arouna’s LinkedIn profile is devoid of any mention of this endeavor. It’s as if the whole operation was created just to give the illusion that Spartan Mosquito was going to rid the world of malaria, a fact that could be used to manipulate reviewers at the EPA.

2. West Nile Education, Eradication & Prevention

WEEP & Recover, a Mississippi non-profit, was also set up two days before the EPA’s consideration of the Pro Tech. It’s run by James Hendry, probably most famous for his other non-profit, Mississippi for Family Values. The WEEP & Recover website and Facebook page are full of slick graphics and videos, most of which feature Spartan Mosquito and, notably, never mention any other mosquito-control company.

Functionally, WEEP & Recover is an advertising arm of Spartan Mosquito. The videos, graphics, and website design are all provided by the branding firm, Unify by Bread. Unify by Bread also produced a heartwarming video about hardware store staff that used Spartan Mosquito products as backdrops. My guess is that all of this was funded by Spartan Mosquito, perhaps channeled through Gunster Strategies. Regardless, somebody gave the nonprofit checks of $5,000 in 2020 and 2021, then stopped. That fits with the brief role the non-profit played for Spartan Mosquito.

In summary, it seems very likely that the EPA was played. And they likely know it.

Suggestions for state pesticide regulators

The EPA says it will not reevaluate the Pro Tech’s registration until 2035, but state lead agencies (SLAs) retain the legal right to require a pesticide company to make label changes to comply with individual state laws, as long as those recommendations are already covered under FIFRA. Below are my suggestions:

- Require Spartan Mosquito to add wording to packaging and website to clarify that the Pro Tech will not completely eliminate mosquitoes. The change is needed because its previous product, the Spartan Mosquito Eradicator, is advertised to kill up to 95% of mosquitoes (a false claim), and consumers who have used Spartan Mosquito Eradicators for years might thus assume that the Pro Tech has the same level of efficacy, if not higher. The EPA has already directed the company to make this change. Spartan Mosquito has so far refused to comply.

- Require company to remove the phrase, “slow release device“, from its website and Facebook page. The “slow release” suggests that the boric acid gradually activates over a month, which is a false statement as far as I know (i.e., boric acid just doesn’t do this). Also, the phrase is not mentioned in the EPA registration and is therefore an off-label claim.

- Require company to remove the phrase, “attractive toxic sugar bait” from its website and Facebook page. To qualify as an “attractive toxic sugar bait”, the Spartan Mosquito Pro Tech would need to attract mosquitoes when natural sources of sugar (flowers, rotting fruit) are present in a yard. As far as I know, there is no evidence that the Spartan Mosquito Pro Tech attracts mosquitoes when it is deployed outside. I.e., even though the tubes do contain sugar and a toxin, it does not appear to be an attractive toxic sugar bait. Also, the phrase is not mentioned in the EPA registration and is therefore an off-label claim.

- Require Spartan Mosquito to change the product name. EPA guidelines prohibit the use of any brand name that implies heightened efficacy. The phrase “Pro Tech” is shorthand for “professional technology” and thus does not comply with FIFRA.

- Prohibit company from using the device’s alternate brand name, “Spartan Mosquito Eradicator Pro Tech”. The reasoning behind this suggestion is that the EPA specifically prohibits the use of the word “Eradicator” in brand names. The name does not comply with FIFRA.

- Require Spartan Mosquito to omit the phrase, “mosquitoes will gather around the tubes”, that is currently printed on the package label. To my knowledge there are no data supporting this claim. I.e., Spartan Mosquito has not demonstrated that mosquitoes are drawn to its tubes when they are deployed outside.

- Require company to clarify what the sugar and yeast are for. If the sugar and yeast are active in some way (e.g., to attract mosquitoes to the tube via the CO2 produced) they should be listed as active ingredients. Also, the yeast will produce ethanol vapors and carbon dioxide, both of which can be lethal to mosquitoes, another reason why the ingredients should be in the active-ingredient category. NB: the company has indicated on forms sent to several states that the yeast and sugar in the Spartan Mosquito Eradicator function as attractants.

- Require company to remove the testimonials on its website. Currently the company features nine testimonials from people discussing their experiences with the Spartan Mosquito Eradicator, a different pesticide product. I.e., given the date when these testimonials were posted on the company’s Facebook page (I spent hours tracking them down), the people would not yet have had the opportunity to test the Pro Tech for the season. This is deceptive.

States should ask Spartan Mosquito for all the data

It’s my understanding that any state can require a company to provide additional experimental data, even for pesticides that have EPA registrations. As the sole example of how this happens, California requested Spartan Mosquito’s data on the Pro Tech and then rejected the registration, making it the only state to prohibit sales of the tube. I encourage all states to ask for these data. They should ask for data from outdoor efficacy trials, proof that the tubes attract mosquitoes outdoors, and proof that tubes produce levels of carbon dioxide capable of attracting mosquitoes for a full 30 days. And for all data that you receive, pay careful attention to whether the experiments are designed with proper controls, have replication, and are done by third-party researchers who are actually qualified to run experiments. I.e., if data are coming from poorly-designed, in-house tests, be skeptical.

I also encourage SLAs to contact Mr. Ajay Kumar at the California Department of Pesticide Regulation. He has gone through all of Spartan Mosquito’s data on the Pro Tech and personally signed off on the rejection of the company’s application to sell it in the state. I suspect he’d share his findings with state pesticide regulators in other states. It would take all of 60 seconds to send him an email. You should also ask him to send you files for study IDs #327922-327936.