Below are some developments relating to Spartan Mosquito’s attractive toxic sugar bait called the “Eradicator”. It’s a tube filled with water, sucrose, sodium chloride, and yeast.

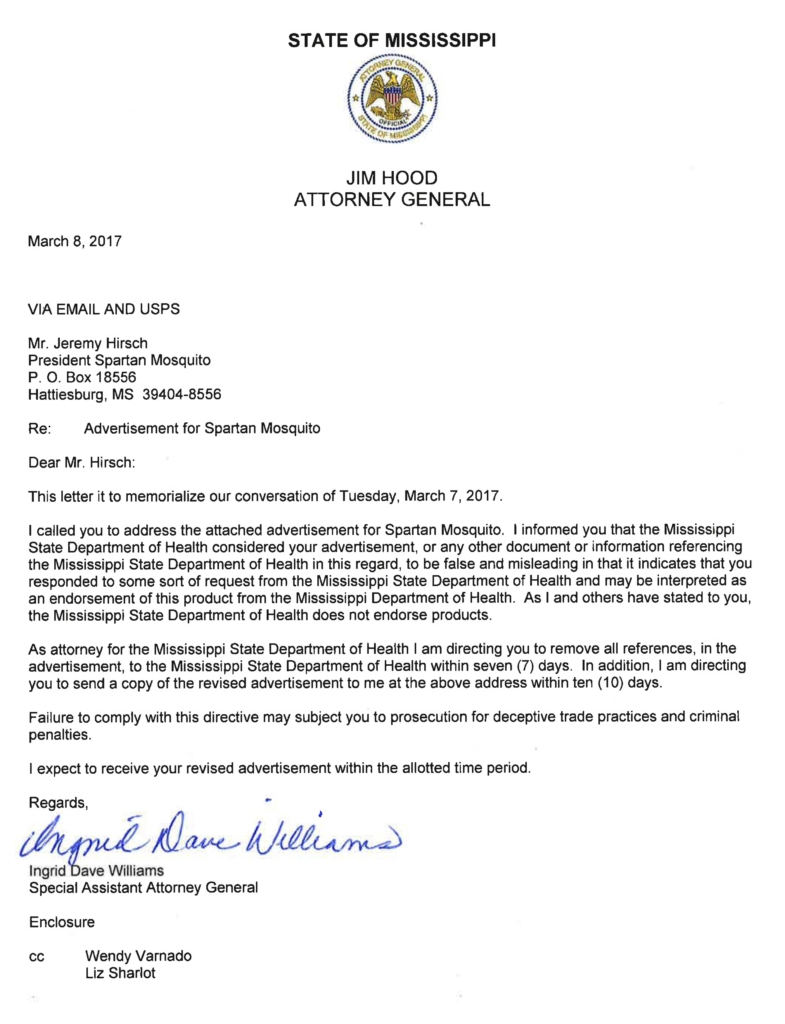

Cease-and-desist order

I was curious whether the Mississippi Attorney General’s office had ever taken legal action against Spartan Mosquito (a Mississippi company), so I submitted a freedom-of-information request and was sent a letter, below, that directed the company to remove all mention of the Mississippi Department of Health from an advertisement.

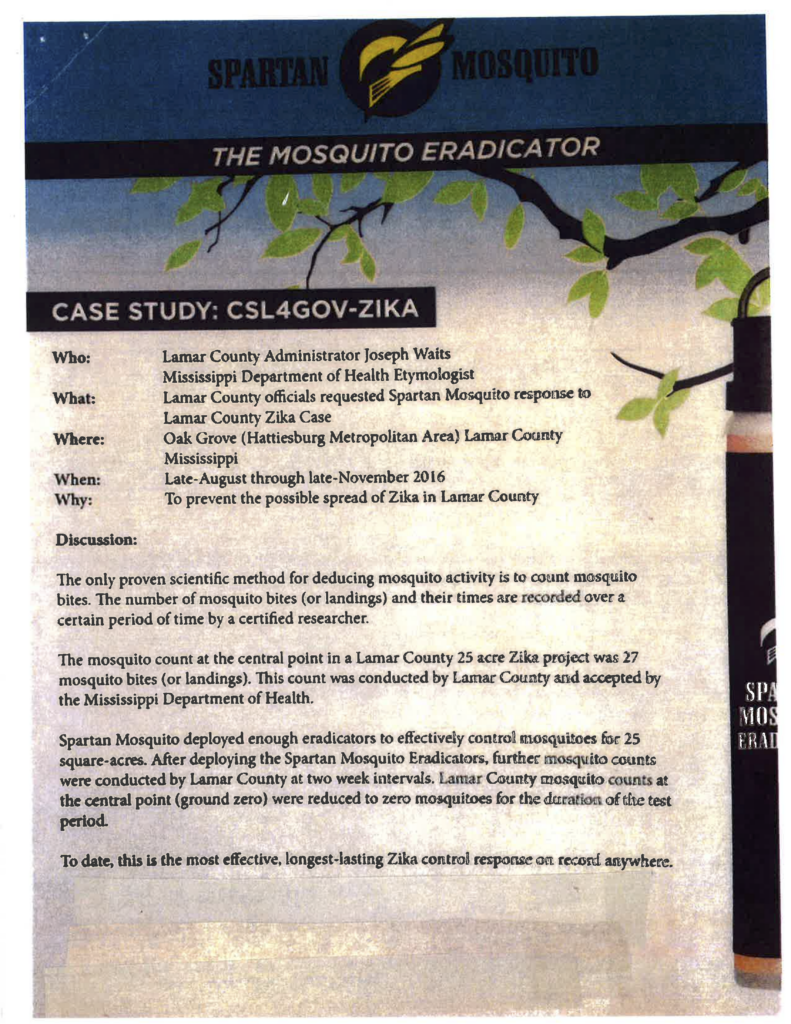

The Attorney General’s office sent the offending ad, too (below), which purported to summarize an experimental test of the Spartan Mosquito Eradicator. The ad asserts that the Mississippi Department of Health’s entomologist was involved and that the Department approved the results — both were false statements. Spartan Mosquito further emphasized a (non-existent) government collaboration by naming the case study “CSL4GOV-ZIKA”.

Zika health claim

As an aside, the Department of Health’s entomologist was indeed at the site, but she was there to coordinate the massive spraying program that the Department of Health was using to minimize the potential mosquito-borne spread of Zika virus around the house of somebody who had the disease. Therefore, the reason there were no mosquitoes in the area is not because there were Spartan Mosquito Eradicators hanging from trees but because the mosquitoes were all killed by months of insecticide treatments. Spartan Mosquito knew the area was being sprayed with insecticide, too, but ignored that detail when it concluded that the presence of the Spartan Mosquito Eradicators resulted in “the most effective, longest-lasting Zika-control response on record anywhere”. Making a health claim violates both EPA and state rules.

Spartan Mosquito repeated the claim in a Facebook ad:

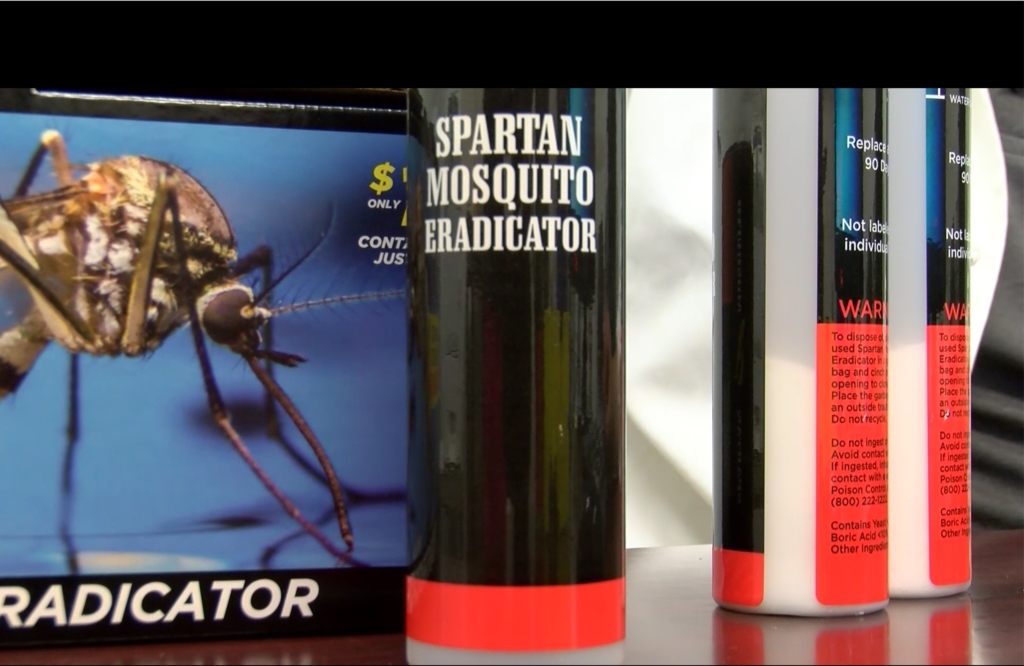

… and in a television segment (jump to the 40-second mark):

Efficacy claims from boric acid formulation

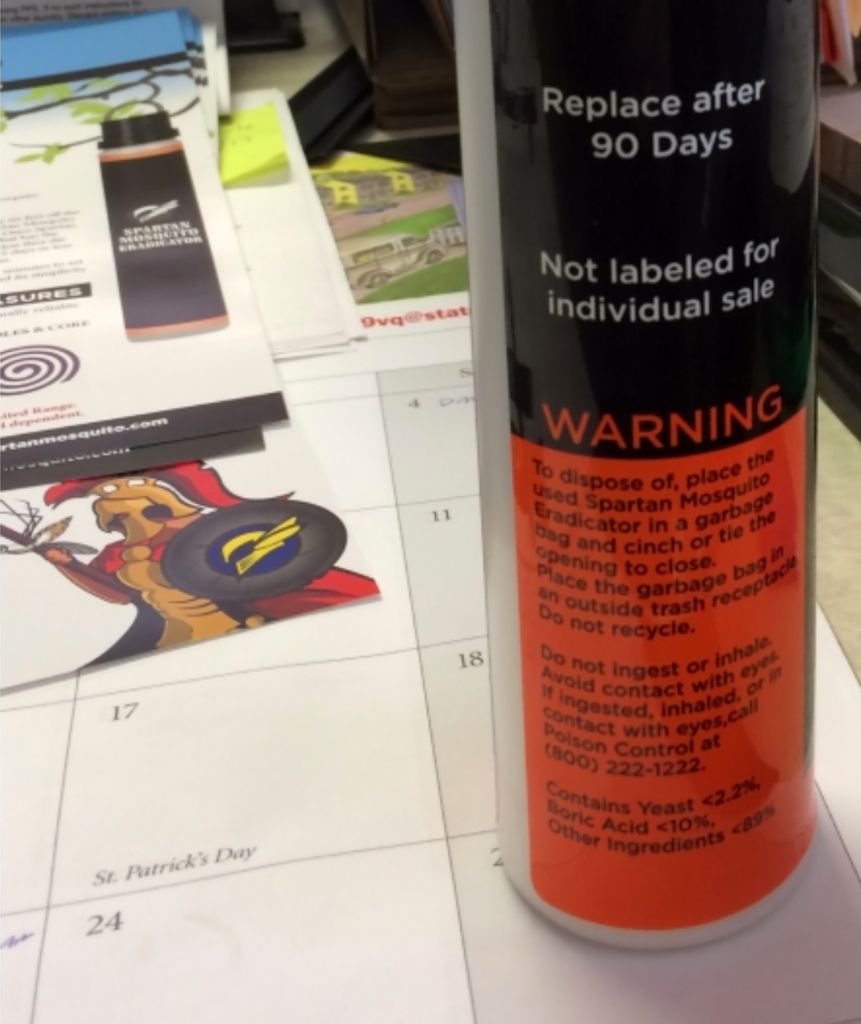

It’s important to note that at the time of the Zika “case study”, the tubes appear to contain boric acid, not table salt. I determined that by freezing the above television clip (@ 1 min 9 secs) and looking at the ingredient list at the bottom of the label.

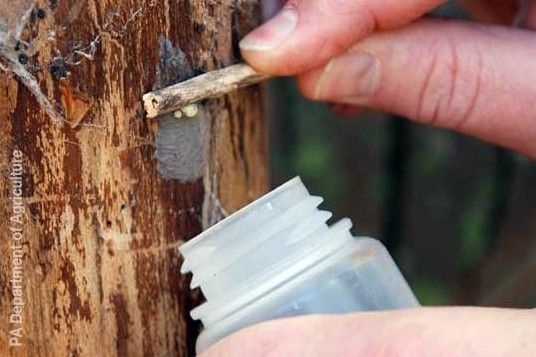

Spartan Mosquito even gave one of its tubes to the Mississippi Department of Health’s entomologist, who took a photograph (below). This photograph confirms that the tubes used at the Lamar County site contained boric acid.

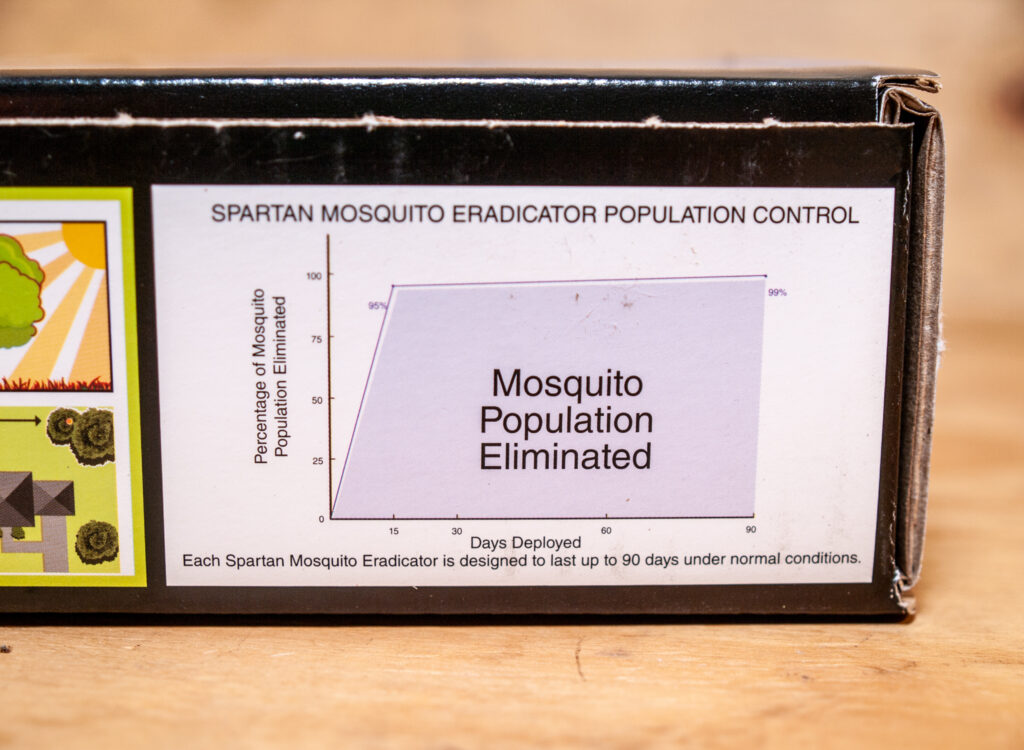

This means that the efficacy claims (“kills up to 95% of mosquitoes for 90 days”) on current boxes of Spartan Mosquito Eradicators are based on a version of the product with a different formulation. And, by extension, the graph is based on the boric-acid case study, too:

Sale of unregistered, boric-acid version?

There’s another consequence of using boric acid (a Federally-regulated pesticide) in early versions of the Spartan Mosquito Eradicator — it means that the company was required to get an EPA registration to legally sell the device in the United States. It didn’t have one. I’m not sure exactly which states the Spartan Mosquito Eradicator was shipped to during this time. Or maybe it was just in-store sales in Mississippi.

States banning the Eradicator

You’d think given all of the above that the device would have been banned long ago, but most states allow the Spartan Mosquito Eradicator to be sold without restriction and with no alterations of its original packaging and claims. And retailers in these states can repeat and amplify those claims (“get your yard mosquito free”) to generate sales.

Sales of the Spartan Mosquito Eradicator have been blocked only in California, Connecticut, Indiana, Kansas, Maine, Montana, New Mexico, New York, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico. States don’t announce why, usually, but one cited false and misleading claims, lack of acceptable efficacy data, and presence of numerous health claims on the company’s website (here are archived snapshots) and its Facebook page (company is in the process of hiding the claims).

Audit of 25(b)-exempt pesticides

A recent initiative by the Association of American Pesticide Control Officials (AAPCO) is likely generating fresh scrutiny of the Spartan Mosquito Eradicator. Per the group’s website, state regulators in Arizona, Indiana, Maine, Mississippi, South Dakota, Washington DC, and Wisconsin have all volunteered to make a list of “minimum risk” pesticides on the market in their respective areas and then evaluate how the products were vetted. The end goal of this exercise is to help all states standardize how such products are approved. The emphasis will be on efficacy data, and AAPCO has 2-pages of guidance on the topic, all of it very sensible. Here’s a sampling of what the group recommends:

- Application should include a complete description of the materials and methods, statistical results, and conclusions.

- “Data must be credible, independently collected, reproducible, and replicated.”

- “Data should include a minimum of three (3) replicates per test.”

- “Data should be generated with the product (formulation) submitted for registration.”

- “Data should include an untreated control.”

- Study director should have actual experience in designing and conducting experiments.

In regards to the latter requirement, to my knowledge Jeremy Hirsch did not have any experience in conducting mosquito trials. At the time of the study he owned a sandwich shop franchise.

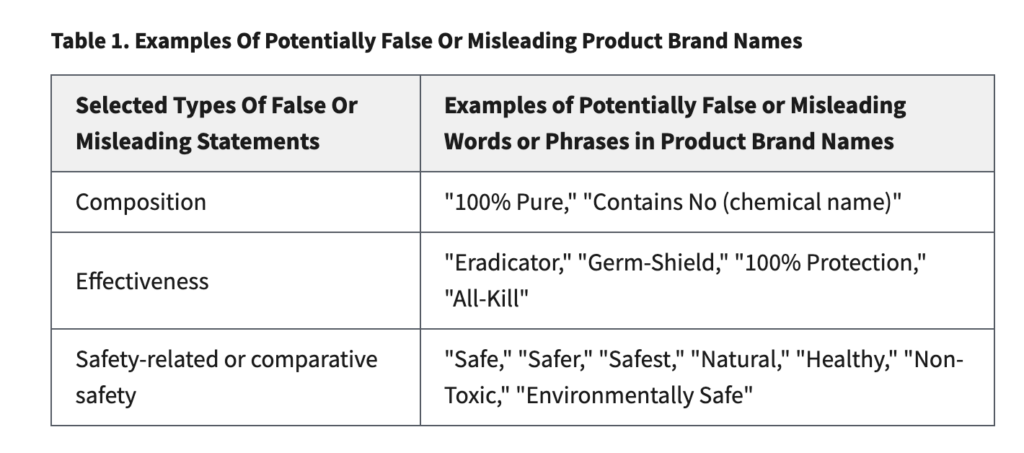

In addition to standardizing the data requirements, participating states will also collect and study products labels. The part of the label that might be discussed for the Spartan Mosquito Eradicator is the name of the product itself. In AAPCO’s guidance, misleading brand names is a concern:

Because “eradicate” means to eliminate entirely, state regulators might reasonably view “Eradicator” as misleading. Indeed, the EPA specifically identified “Eradicator” as a misleading brand name in 2002, years before the Spartan Mosquito Eradicator came to market.

What’s especially interesting about the audit is that Mississippi, Spartan Mosquito’s home state, is participating. And, according to the Mississippi Bureau of Plant Industry, Spartan Mosquito never submitted efficacy data even though doing so is a requirement (screenshot of its rules is below).

In contrast, some of participating states have seen the efficacy data and have banned sales of the device. I think the audit process (which involves numerous rounds of reports and meetings) could easily trigger stop-sale orders in those states that haven’t yet appreciated the device’s shortcomings. I suspect it might also trigger scrutiny of the company’s new version, the Spartan Mosquito Pro Tech, which reverts to the original formulation of boric acid.