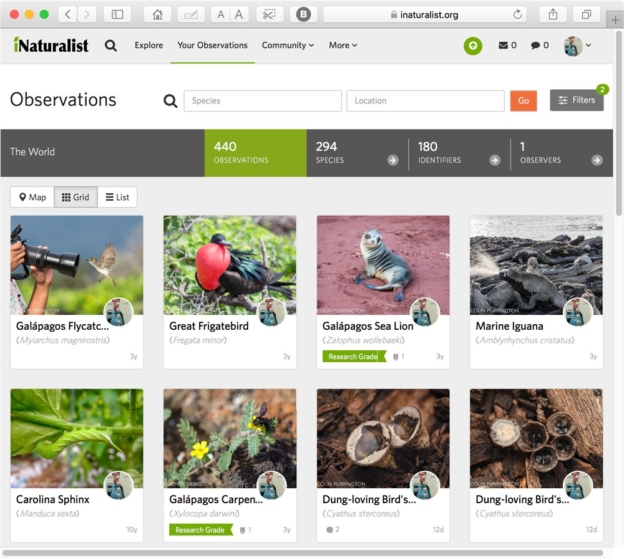

iNaturalist is a free site that allows nature fans to share — and learn more about — organisms they’ve found on hikes, in their yards, or attached to their bodies. All you do after signing up is upload a photograph, make an identification guess (or not — no pressure), then solicit ID help from the built-in AI as well as from the approximately 80,000 active users, some of whom know how to identify things. But it’s a community, so you (yes, you) can also weigh in on IDs for photographs taken by other members (but again, no pressure).

Below are some reasons to give it a try. The first several are general, the later ones for scientists or professional naturalists.

1. Get your photographs identified

If you post nature pics on the Internet, it’s so much better to caption them with either common name or Latin name so that people can easily find the image in Google searches and such. Plus people just like to know. Saying something is a “seal” is fine but when you have a Galápagos sea lion you should say so (because there 12+ species of seal). You should also use iNaturalist even if you think you know what it is. E.g., to make sure you’ve captured a Galápagos sea lion not a Galápagos fur seal, both of which are in the Galápagos. Using iNaturalist to get IDs is also better than posting a photograph to Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook and asking the world, “Anyone know what this is?” Your followers on those other social media accounts might not be giving you accurate information. Just saying.

2. Educate yourself

Nature in the general sense is nice and all, but after you figure out exactly what something is you’ll have the magic key to find further information that might be truly interesting. E.g., Nazca boobies (Sula granti) have an interesting name but if you Google the name you can learn that males court females by offering them sticks and stones even though this species doesn’t even build nests (behavior is an evolutionary holdover from ancestors that did, presumably). Another reason to search for more information is to be reminded that for the vast majority of species, even rather common ones, we know surprisingly little. And knowing this is a good thing because then youngsters and young at heart will realize that going into a biology-related field is a way to explore the unknown. Appreciating and protecting life on earth is easier when you know the details, and you can’t get them just by knowing a lot about polar bears and other charismatic megafauna.

3. Use and improve your ID skills

Your friends and family might roll their eyes whenever you call out bird names when one zips by, but those identification skills are cherished on iNaturalist. Nobody will make fun of you! By providing IDs you are helping those new to nature get more out of nature and in, perhaps, helping voters and politicians appreciate see that policies can directly help or hurt particular species on the planet, even in your home town. You will also be providing IDs to over-educated professionals who might be posting pics of organisms outside their research speciality, but who might someday return the favor. iNaturalist also provides an environment where you can teach yourself how to ID new organisms. E.g, I learned that great frigatebirds (Fregata minor) can be distinguished from magnificent frigatebirds (Fregata magnificens) by their green sheen. Tricks like this can be useful when traveling to new places, and you can use iNaturalist like a study guide to prepare for such trips. E.g., if you’re shelling out tens of thousands of dollars to travel to exotic places like the Galapagos, spend the year before learning the flora and fauna so that once you land you know what’s going on (your guide might not). All you do is subscribe to the place and challenge yourself to learn how to identify submissions (you’re going to need a few books, too).

4. It will make you happier and healthier

iNaturalist is like a mental Fitbit, recording what you’ve seen instead of the number of steps. And then when you revisit memories of being outside you’ll become happier! At least that’s the research. I’m just hand-waving here that iNaturalist will make those memories fonder and more vivid, but it’s not too much of a stretch. At the very least it’s true for me. It’s also reasonable to think that if iNaturalist motivates you to go outside more often, losing excess weight or achieving those 10,000 steps will be that much easier. But I’m not a real doctor, so consult your physician to see whether nature is right for you. And please check for ticks (take a photo if you find them).

5. Meet interesting people

People who are active on iNaturalist are by definition curious and have open minds. Those are the peeps you are looking for these days. Right? Unlike some other social media places, users are also actual people … and some of them live near you. So when you see on iNaturalist that there will be a meet-up at a local park, join them. Or if you’re in one of those areas where iNaturalists are rare and shy, you can organize an even and invite folks.

6. Be a better parent

If you have young kids who are still fascinated by nature instead of electronics and air conditioning, encourage this interest by modeling a similar interest, even if feigned. If, for example, your little girl is fond of spiders, take pics of the ones she finds, upload to iNaturalist, then show her the eventual identification results and help her Google the species name for more information. You don’t need to have a biology degree to do that.

7. Be a better teacher

If you’re a biology teacher, you really, really need to become proficient in iNaturalist. E.g., if you teach kindergarten and want to tap into kids’ innate interest in nature, submit pics of organisms that your students find in the classroom or during recess. You can say each Monday, “Good morning boys and gorls — find me an organism!” You take a pic, then share ID, courtesy the folks on iNaturalist, with your students on a subsequent day (oh, the suspense!). Pair those IDs with an age-appropriate book on very hungry caterpillars, itsy bitsy spiders, or whatever. And if you’re a college teacher, you could assign a local, interesting species to each of your students, tasking them with (e.g.) figuring out how to ID it and to explain its distribution and conservation status … and after several weeks ask students to make presentations supplemented with natural history tidbits from the primary literature. Ideally, an exercise should challenge the students to contribute to iNaturalist (e.g., if they can make themselves an expert for species X, they should be able to weigh in on IDs). There are thousands of ways to incorporate iNaturalist into classrooms and homeschooling. iNaturalist has a page to get you started. Here’s a video tutorial if you like to watch.

8. Manage your land better

If you manage a natural area, you can use iNaturalist to create a permanent, dynamic, searchable database of all the species found there. It’s probably your job to do that in some regard, but iNaturalist allows you to crowdsource the task — just ask to visitors to upload their pics to iNaturalist and, voila. It’s really easy to set it up: draw a polygon around your area in Google’s MyMaps, export KML map file to desktop, upload map to iNaturalist to create a “new place”, then create a Project that automatically shows all observations in your area. The setup process takes approximately 15 minutes. If this sounds useful, just do it right now but tell your boss that it took weeks.

9. Get alerts when a species is observed

If you are in charge of tracking the spread of spotted lanternfly, emerald ash borer, or any of the other thousands of invasive species that keep biologists up at night, just “subscribe” to that particular taxon for the park, county, state, or country of interest, then sit back and wait for the email indicating that somebody has found that species area of interest. It’s so much better than all those report-an-invasive apps or 1-800 numbers that require people to know that something is invasive and also be motivated to download an app or look for number to call. You can also use the subscription feature to monitor a place for a species that might be your research focus (e.g., perhaps you want to know when the Galapagos carpenter bee colonizes a new island).

10. Mine it for data

There over 12,700,000 observations on iNaturalist, and that means if you’re looking for something rare or just trying to quantify something, you might be able to extract data to address a hypothesis from the comfort of your couch. For example, you might want to know whether marine iguanas close their eyes when they sneeze but don’t want to make the trip to the Galapagos to find the answer (though you probably do). You can also track when a species is first seen flowering in an area for the past 10 years … which might have something to do with climate change. Or you might notice that there’s a new, undescribed species (!), in which case you can contact the observer, write a paper together, and be famous (some examples). Finally, if you need DNA or measurements from a particular species you can hit users up to do this. My suggestion to scientists and teachers who are too busy is to just sign up and then subscribe to your study organism, something that will take 5 mins, max. Once you start seeing variation, natural history comments, and interesting questions from users you’ll be hooked. The are numerous ways to make it interesting and useful … you just have to toggle the settings in the right way.

I have more reasons why you should be using iNaturalist but 10 is the limit for lists of 10 so I’ll end here. Thanks in advance for sharing this post with your friends. We need them, too.