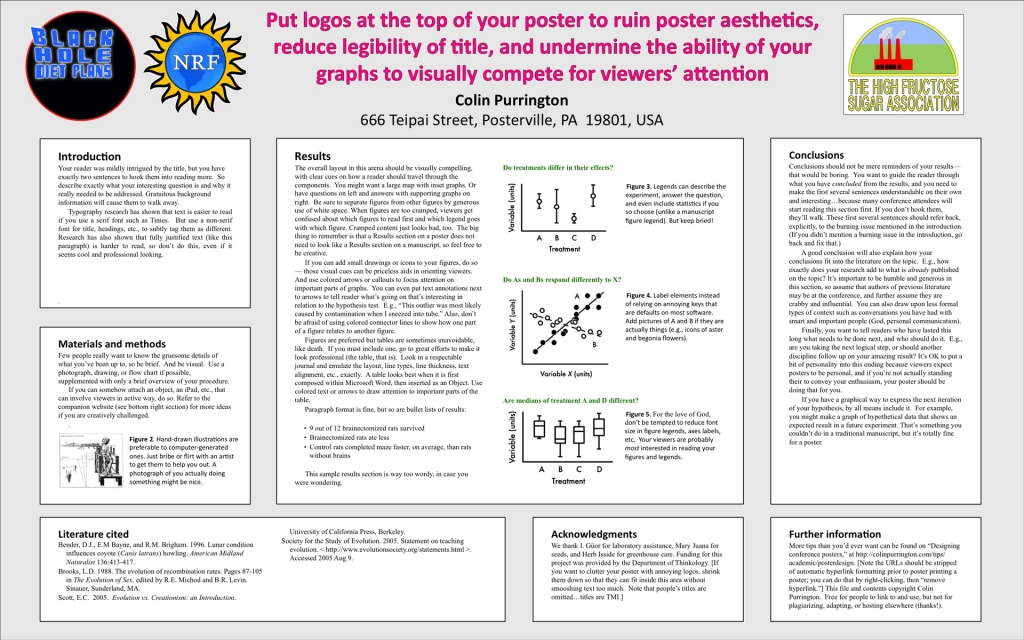

One of my many pet peeves about conference posters is the placement of logos at the top, a practice encouraged by almost all templates on the internet, by mentors who think it’s really cool, and of course by the funding institutions, colleges/universities, and conference organizers who want to see their logos featured. Logos at the top are bad because (1) titles are squished and (2) the charts, illustrations, and photographs have trouble competing visually. Here’s an example:

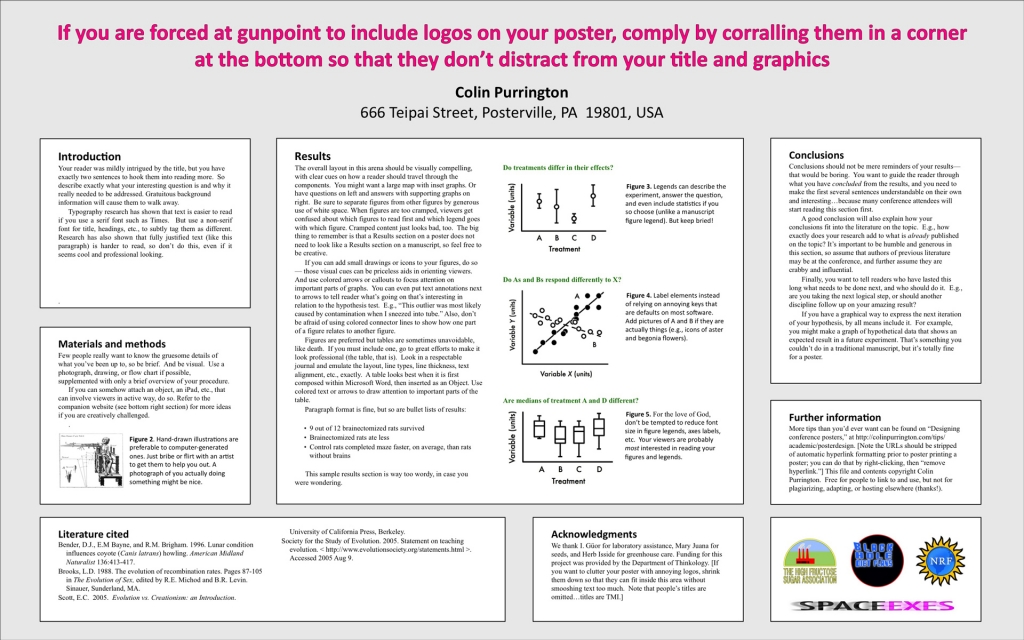

If you absolutely must include a logo on a poster, corral them into a small area at the bottom of the poster, like this:

Please share this post with anyone who might be at heightened risk for logo abuse. If you want more tips on poster design, please see my Designing conference posters page.