Ways to kill nymphs and adults

Flyswatter: Nothing beats a flyswatter. If you are protecting just one tree, insert a pushpin into the trunk so that you have a convenient place to hang it. Make it part of your morning routine.

Rubber bands: These work like a charm and are mildly fun. Be careful of fragile leaves, though — rubber bands can cause more damage than the insects.

Lid-container technique: Fill a container with soapy water and use the lid to motivate them to leap inside. You can kill thousands this way once you get the hang of it.

Cordless stick vacuum: A long extension arm of a stick vacuum is ideal for reaching into vegetation. I own a Dyson cordless stick vacuum but there are lots of options (e.g., on Amazon).

Backpack vacuum: If you are serious about controlling spotted lanternflies, go buy yourself a battery-powered backpack vacuum that has a large, clear repository. Then you can stroll around your yard in the evening and suck up thousands over a short period of time. A shop-vac will also work in a pinch but is much less convenient because of the cord. PRO-TIP: buy a Ghostbusters costume for your gullible child and tell them sucking up lanternflies is good practice.

Leaf vacuum: Maybe something like the Black and Decker 36v Cordless (GWC3600L). I don’t own one of these but they look fun. Amazon carries a lot. Most hardware stores can set you up. Note that most leaf vacuums shred, so be prepared for some goo.

Circle traps: These involve a little time to make but they look fantastic. Here’s a page that gives detailed instructions.

Sticky tape: I strongly advise against the use of sticky tape and spreadable goo. Sticky surfaces will certainly kill some spotted lanternflies but in my experience, not that many. The real outcome is that thousands of other, smaller insects will get trapped, which in turn attracts other, larger insects keen on eating the trapped, squirming insects. Then insectivorous birds come and get trapped (click here if you doubt me), as will bats (click here if you doubt me). Many birds and bats will likely escape but will be covered with goo and may die later. If you are unconvinced that trapped birds and bats are a problem, I urge you to Google videos of such so that you can see them suffering. Those videos are just too horrible to link to. Also, tape can leave permanent marks on your trees.

Bug-A-Salt rifle: I don’t own one of these, sadly, so I can’t absolutely guarantee it will work. But I’d be really surprised if they didn’t. I think it would make the daily lanternfly patrol really fun, and everyone in the family would want a turn. You can buy them on the Bug-A-Salt website and on Amazon. Do not buy one if you have children in the house. You can definitely shoot your eye out with these things.

Airsoft gun: Don’t get one of these if you have kids. But if you have a semi-responsible adult who enjoys killing spotted lanternflies, this would be a sweet gift. I see them as especially valuable in killing the adults that are high up in branches, out of the range of your vacuum. Buy (1) only biodegradable pellets, (2) opt for lightest pellets you can find (to minimize tree damage), and (3) wear safety goggles (the pellets ricochet off tree trucks). Note that Airsoft guns are illegal in some areas (e.g., Arkansas, parts of Michigan, Washington D.C., San Francisco, Chicago, NYC). And, of course, you always run the risk of being shot by police even if you are on your own property. To minimize the risk of being shot, DO NOT remove the blaze-orange tip.

Electric flyswatter: I own one of these and they work really well on large flies so I don’t see why they wouldn’t work on spotted lanternfly nymphs. I suspect adults wouldn’t care. There are dozens for sale on Amazon.

Pathogenic fungi: There are at least two fungi (Beauveria bassiana and Batkoa major) that seem to infect spotted lanternfly, so it might be possible to coat them with a powder or a spray and watch them slowly die. Unfortunately, the experiments on whether this is worthwhile are not yet done (or not yet published), so I can’t guarantee success. But in the wild, these fungi seem to do their thing well. I’m going to buy some Beauveria bassiana from Amazon for the 2020 season, just for giggles. Batkoa major is not yet for sale, I think. Here’s an adult I found that I think is infected.

Dawn soap: This is one of many home remedies that has gone viral but should not have. Detergents pollute waterways and can also damage plants.

Propane torch: This looks extremely satisfying (see video) but it’s just going to result in forest fires and home losses. Don’t be that guy. If you’re married to that guy, hide the propane tank.

Chinese mantids: Please do not buy mantid egg cases and release in your yard. Chinese mantids are invasive and mainly eat butterflies (even monarchs, even hummingbirds). They are not beneficial insects, despite claims to the contrary on Pinterest.

Insecticides: Unless you own a vineyard, spotted lanternflies are a nuisance insect, not a health threat. And they do not seem to be killing trees or other plants. So I do not recommend spraying them with insecticides. A typical homeowner (I include myself) is not in a position to apply pesticides safely and in an environmentally-responsible way. You’d just end up killing all the pollinators and fireflies in your yard, plus pollute local streams. It’s also, in my opinion, futile to spray: there are likely thousands of individuals in neighboring yards that will reinvade your yard in the days after you nuke it. But if you do spray, please refer to Penn State’s guidance.

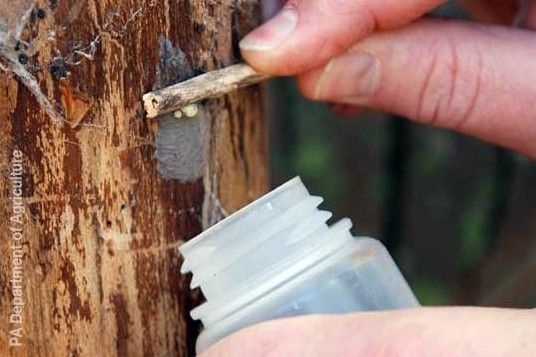

I also don’t recommend that homeowners treat male tree-of-heavens (Ailanthus altissima) with systemic insecticides to create “bait” trees. It seems like a perfect solution: because tree of-heaven is their favorite host, you could potentially kill thousands of adults as they arrive to feed on insecticide-laced trees. And it’s touted as being safe for other insects because few other insects eat the foliage. The huge downside, in my opinion, is that many systemic insecticides find their way into nectar and pollen, and thus these bait trees will likely poison large number of pollinators (you’d just never know it). This downside should be especially worrying to suburban beekeepers because those chemicals could potentially end up in honey. And, more generally, the bulk of systemic insecticides is likely washed into waterways or taken up by nearby plants in your yard, not just tree-of-heaven trees.