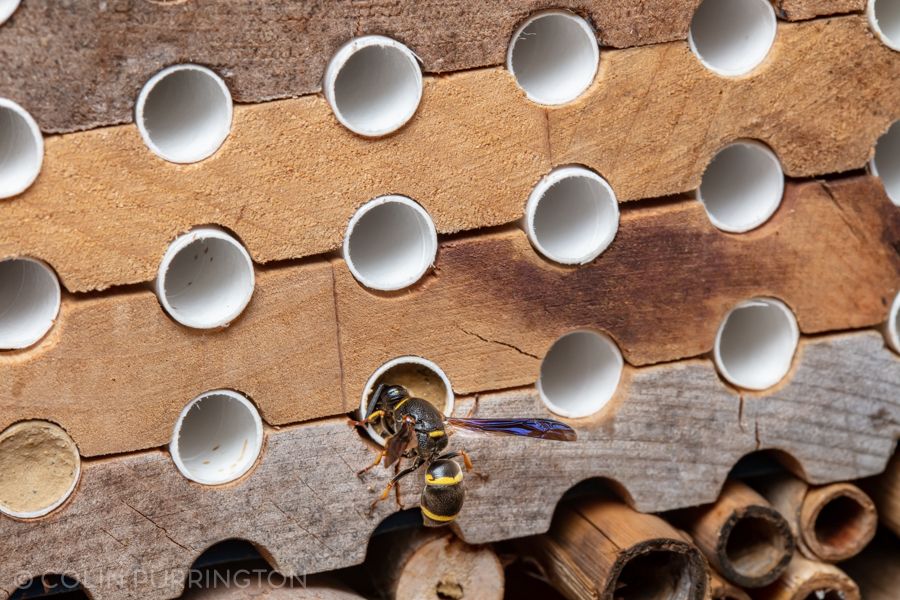

Here are some of the pics I’ve taken at bee hotels over the past several years. Sharing in case other beekeepers might recognize residents in their own hotels. There were bees, as one would expect, but also wasps, flies, and beetles.

Horn-faced mason bee (Osmia cornifrons). Very common at my hotels. Introduced from Asia in the 1970s. Details at BugGuide.

Taurus mason bee (Osmia taurus) are also common and also introduced. Details at BugGuide.

Giant resin bee (Megachile sculpturalis). Yes, also introduced, though more recently (~1994). Details at BugGuide.

Mock-orange scissor bee (Chelostoma philadelphi). So named because it prefers to collect pollen from trees in the genus Philadelphus (mock oranges). This is the only native member of the genus in the United States. Details at BugGuide.

Ancistrocerus antilope has shown up a few times at my hotels, but apparently prefers to nest in sumac and elder stems. It also is reported to use old mud-dauber nests. They are fun to watch because they provision nests with caterpillars. Details at BugGuide.

This is Euodynerus “Species F” at the moment. I.e., it’s one of several undescribed species in the genus (details here). Its biology is apparently unknown, so I’m hoping to get more of them in the future.

Parancistrocerus histrio is another wasp that feeds caterpillars to its brood. Details at BugGuide.

Auplopus mellipes provisions its nests with spiders. For a wonderful overview of their biology, please see post on Eric Eaton’s blog. (While there, I noticed he has a new book on wasps.)

Euodynerus schwarzi provisions nests with caterpillars. For identification tips, see blurb by Matthias Buck et al.; more pics are at BugGuide.

Euodynerus megaera is extremely similar to the above species but has black tibiae. At least females do (males are much harder to distinguish). It’s also a collector of caterpillars. More details by Buck et al.

Brown-legged grass-carrying wasp (Isodontia auripes) provision their nests with tree crickets. As their name suggests, they also carry grass, which they use to pack and seal the brood chamber. Details on BugGuide.

Here’s a photo of the grass-carrying wasp’s nesting plug that I took at Longwood Gardens. They have a beautiful bee hotel with hundreds of cells but as far as I could tell, only a few wasps had moved in.

Trypoxylon collinum provision their nests with spiders. Unlike many wasps and bees, the males in this genus actually help out around the nest. For details, please see this Instagram post. BugGuide has a page for the species but it contains little information.

Cuckoo wasp (Chrysis sp.). They are absolutely adorable. That said, they are also parasites of the above bees and wasps that are nesting at the hotel. They are very difficult to identify, so even getting them down to genus is rare. Here’s BugGuide’s page on the family.

The club-horned cuckoo wasp (Sapyga louisi) is another frequent parasitic wasp at my hotels. This one is patiently waiting to gain entrance to the nest of a mock-orange scissor bee. Details on BugGuide.

Leucospis affinis is another parasitic wasp that is almost always lurking around my bee hotel. It’s oddly variable in size. More details by Ari Grele at Insects of Cornell, at BugEric, and BugGuide.

Monodontomerus sp. (in Chalcidoidea) are extremely common parasites of mason bees. Please see this post at Nurturing Nature for great video and description of their life cycle. Additional details at BugGuide.

Digonogastra sp. These braconid wasps are parasites, but I’m not positive the ones I’ve seen at my bee hotels are targeting any of the residents. But they’ve shown up on at least two occasions so I think it’s a possibility.

Amobia sp. are flesh flies that develop on the provisions inside (for example) Trypoxylon nests. I’m not sure whether the larvae also eat the wasp larvae, but I’d suspect so. Details at BugGuide.

Houdini flies (Cacoxenus indagator) are newly introduced to the United States and are likely to ravage mason bee nests and the crops that depend on them for pollination. If you have bee hotel, this fly is reason #1 why you should use removable paper tubes that allow sorting of infested and uninfested brood cells. Without paper tubes your bee hotel will likely be a Houdini fly hotel. Crown Bees has information on how to clean your tubes.

Skin beetles (Dermestidae) are scavengers but can become serious pests of uncleaned mason bee hotels. Yet another reason to use only paper tubes fitted inside drilled holes, combined with a thorough cleaning of entire hotel (e.g., soak in bleach, scrub). Details on skin beetles at BugGuide.

The above is probably less than 1% of the species that might be found at a bee hotel that had a range of nesting-hole diameters. Noticeably absent are leaf-cutter bees, so that’s my photo resolution for 2021.

Note that almost everyone calls these hotels “bee hotels”, but in my experience the majority of the residents are wasps. That’s totally fine with me. Wasps are pollinators, too. And wasps tend to be more photogenic and possess more interesting life histories if you ask me. In related news, I’m really looking forward to reading Heather Holm’s new book, Wasps: Their Biology, Diversity, and Role As Beneficial Insects and Pollinators of Native Plants.

For my full collection of photos at bee and wasp hotels, please click on button below.