One reason why there’s an Antibiotic Awareness Week every November is to alert people to the unfortunate outcome of antibiotic overuse: the evolution of strains of bacteria that are resistant to the drugs. I.e., when millions of people each year coerce their physicians to prescribe antibiotics for viral and fungal infections, bacteria that are present in their bodies (but that are not causing disease) can evolve to survive the drug. Then when others get sick from these mutant strains, they die. It is estimated that 35,000 people in the United States die every year from infections of drug-resistant bacteria. I believe the worldwide estimate is close to 700,000.

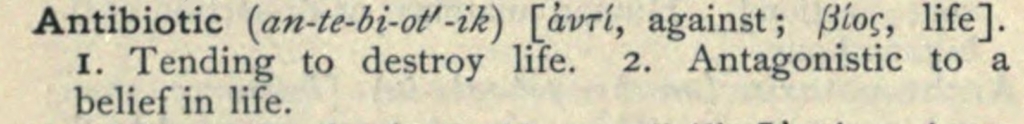

Why are so many people confused about what antibiotics kill? I blame the word. Unlike, “antifungal” (acts against fungi) and “antiviral” (active against viruses), “antibiotic” doesn’t provide a clue about what it kills. Rather, it sounds like a drug that might kill lots of different types of organisms. Just as “biology” is the study of all life — not just the study of bacteria — people assume “antibiotic” is a killer of all life. Indeed, that’s how the word was originally defined.

Antibiotics kill microbes

The history of antibiotic in the medical sense begins in the 1890s, in France, as the adjective, antibiotique. Here’s a 1907 definition, in English, that shows that all life could be considered the target:

In most usage, however, the word was restricted to microorganisms. Then, in a 1942 paper, S.A. Waksman did what I gather was rather important at the time (or at least to himself): he made antibiotic into a noun. Here’s how he defined it (I’ve added the bolding):

“An antibiotic is a chemical substance, produced by micro-organisms, which has the capacity to inhibit the growth of and even to destroy bacteria and other micro-organisms.”

In this an other papers, Waksman explicitly included other microbes. However, microbiologists over the next few decades began to refer to antibiotics as substances that kill only bacteria, a usage that is now popular among most biologists, doctors, and health organizations. But the old meaning — that antibiotics kill all kinds of microbes — still survives as the dominant definition outside academia and hospitals.

Here’s the problem: most biologists and doctors have no idea that the restrictive definition hasn’t been adopted by the general public. In my experience, biologists and doctors even get rather angry when confronted by this fact. To them, it’s fake news. Their reluctance to acknowledge this fact makes it hard for them to grasp the main reason why the public wants antibiotics so badly. Their denial of the fact also makes it hard to design Antibiotic Awareness Weeks that actually raise awareness.

Many dictionaries still say antibiotics kill more than bacteria

Not surprisingly, when curious people look up the definition of antibiotic, many entries still reflect the meaning that has endured for over a hundred years. Here are just five examples (there are thousands):

- “a medicine (such as penicillin or its derivatives) that inhibits the growth of or destroys microorganisms.” — Oxford English Dictionary

- “a substance able to inhibit or kill microorganisms” — Merriam-Webster Dictionary

- “any of a large group of chemical substances, as penicillin or streptomycin, produced by various microorganisms and fungi, having the capacity in dilute solutions to inhibit the growth of or to destroy bacteria and other microorganisms, used chiefly in the treatment of infectious diseases.” — Dictionary.com

- “An antibiotic is defined as any chemical substance that is able to kill bacteria, fungi and parasites, and can thus be used against prokaryote and eukaryote organisms.” — DifferenceBetween.net

- “A chemical substance that is important in the treatment of infectious diseases, produced either by a micro-organism or semi-synthetically, having the capacity in dilute solution to either kill or inhibit the growth of certain other harmful micro- organisms. — Academic Press Dictionary of Science and Technology

Awareness campaigns sometimes define antibiotics broadly

Even people crafting Antibiotic Awareness initiatives sometimes indicate antibiotics are antimicrobial (= treat a variety of infectious agents). Below are just several examples:

- “Antibiotic resistance happens when germs like bacteria and fungi develop the ability to defeat the drugs designed to kill them. That means the germs are not killed and continue to grow.” — About antimicrobial resistance (CDC)

- “Millions of people in the United States receive care that can be complicated by bacterial and fungal infections. Without antibiotics, we are not able to safely offer some life-saving medical advances.” — Antibiotic-resistant infections threaten modern medicine (CDC)

- “Antibiotic-resistant germs can spread in the environment. Aspergillus fumigatus, a common mold, can make people with weak immune systems sick. In 2018, resistant A. fumigatus was reported in three patients.” — The interconnected threat of antibiotic resistance (CDC)

- “Antibiotic resistance is the ability of a micro-organism (such as bacteria) to stop an antibiotic from working effectively.” — What is antibiotic resistance? (NSQHS)

- “Antibiotics are drugs of natural or synthetic origin that have the capacity to kill or to inhibit the growth of microorganisms” — Responsible use of antibiotics in aquaculture (United Nations)

As an aside, for an issue that has such clear relevance to people needlessly dying, failure to convey a crisp, error-free message about what antibiotics can and cannot do is a problem. I would strongly urge governments and health organizations to recruit some actual biologists to proofread their Antibiotic Awareness Week output. Don’t give that job to a committee populated by non-biologists.

The level of confusion over antibiotics is stunning

Biologists and physicians tend to be overeducated and hang out with (and marry), overeducated people. As a result, they often go through life vastly overestimating the science literacy of everyone else. Luckily, there are polls.

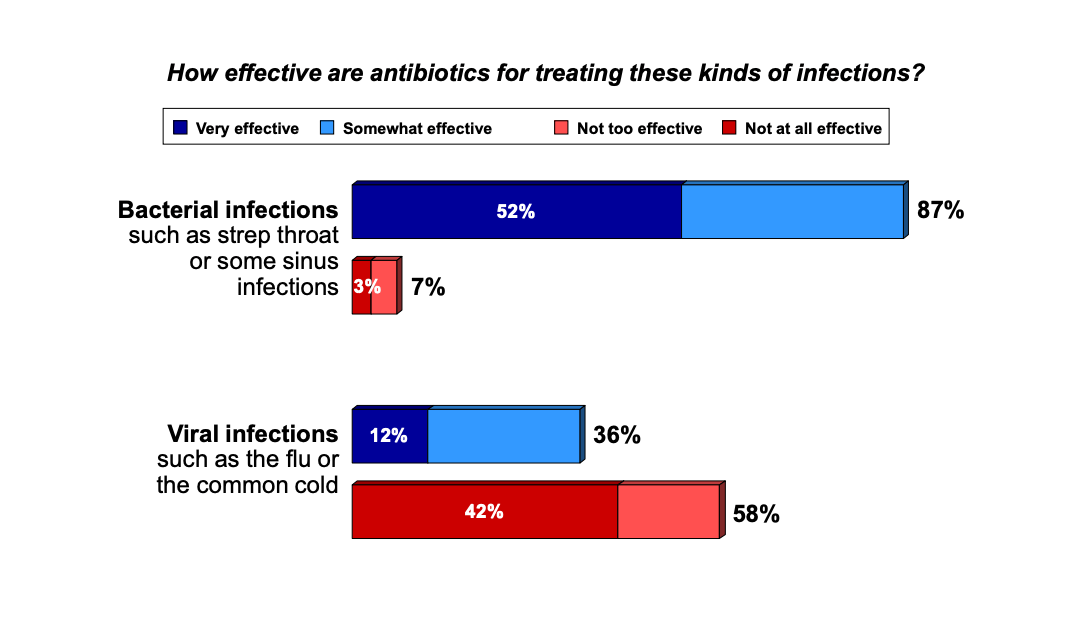

For example, a 2012 Pew study that found that 36% of Americans think antibiotics can treat viral infections:

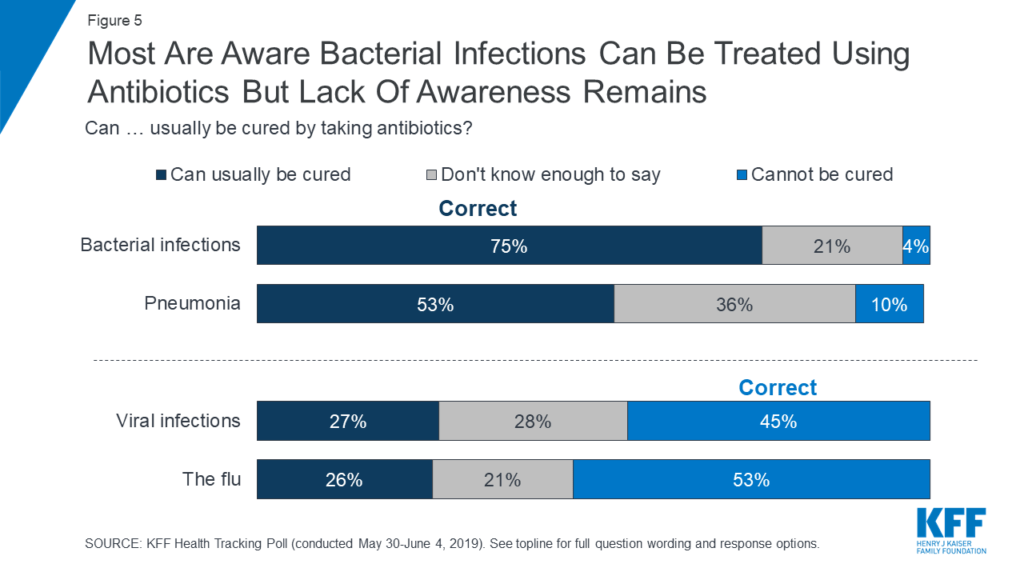

That was seven years ago — have all the Antibiotic Awareness Weeks since then succeeded in educating Americans about antibiotics? No. A 2019 Kaiser Family Foundation poll only 45% of participants knew that antibiotics cannot treat viral infections:

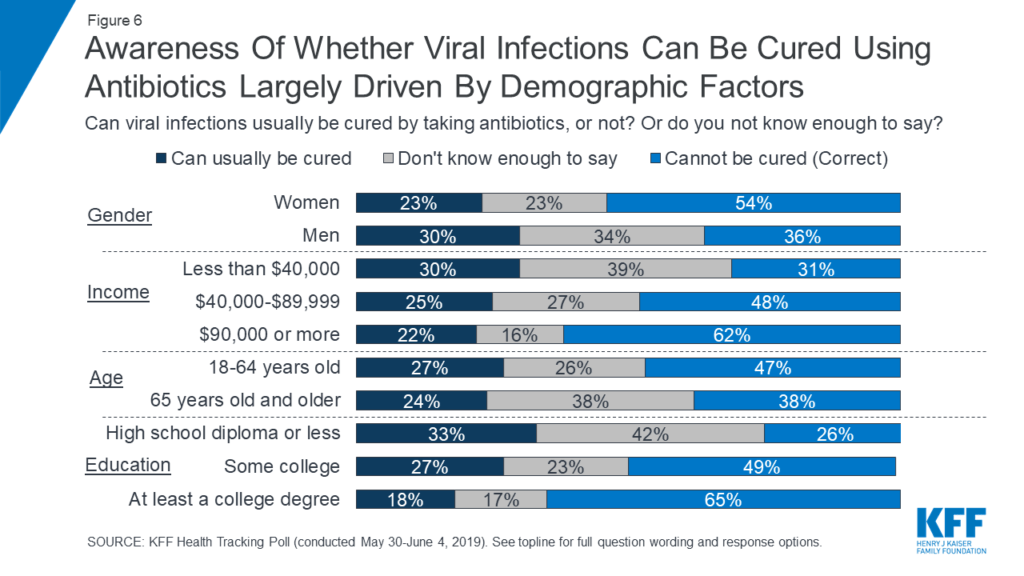

As an interesting aside, men are especially prone to thinking that antibiotics treat viral infections, with only 36% knowing the correct answer versus 54% among women.

Ignorance is not just for Americans, too. A 2010 publication reports that 53% of Europeans believe that viral illnesses can be treated with antibiotics (and 11% weren’t sure). That number rises to 60% in Poland (Mazińska et al. 2017) and 67% in Malaysia (Oh et al. 2011). These numbers probably underestimate the problem, too, because some people (e.g., over 87% in Cameroon) also think that antibiotics work against all microbes, not just viruses.

Ignorance about what antibiotics kill can come in different flavors, and I therefore believe it’s important to understand why people are ignorant. Some people, for example, think that viruses are bacteria (perhaps 10%, per Carter et al. 2016). Other people might think that although antibiotics are designed to kill bacteria, they might have some smaller, beneficial effect in treating other infections (this can actually be true for some viral infections and malaria). Both of these misconceptions can probably be addressed by yearly doses of Antibiotic Awareness Week pushed out by health organizations.

How to provide better antibiotic awareness outreach

A decade of Antibiotic Awareness Weeks in multiple countries seems to have failed in changing the public’s view that antibiotics kill viruses (Mason et al. 2018). I believe the failure is, in part, because Antibiotic Awareness Weeks do not directly confront the confusion caused by the word, “antibiotic”, itself. I have five suggestions on how to improve outreach.

1. Clearly state that antibiotics are substances that kill just bacteria

If you are in charge of running an antibiotic awareness initiative, fully embrace the fact that the majority of the population doesn’t accept that antibiotics treat only bacteria. So give a clear definition of antibiotics. I’ve looked at hundreds of web pages, flyers, and movies pushed out by awareness campaigns, and a painfully large percentage of them fail to say that antibiotics kill only bacteria. It also wouldn’t hurt to say that viruses and fungi are not bacteria. Seriously, why not?

2. Use the word “antibacterial”

An easy way to clarify what antibiotic means is to just put “antibacterial” in parentheses at key places in your outreach. E.g., “Antibiotics (antibacterials) are useful in treating some infections.”

3. Change name to “Antibacterial Awareness Week”

Perhaps the best way to avoid the confusion about antibiotics is to not bring up the word in the first place. Just call it, Antibacterial Awareness Week and use “antibacterial” in place of “antibiotic” in all instances. An example of this approach is demonstrated by the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group — by choosing “antibacterial” the group instantly avoids all confusion about the focus of their group. I.e., if they had used Antibiotic Resistance Leadership Group, instead, people would likely assume the group was interested in all types of antimicrobial resistance.

For the same reason, physicians should opt for the word, “antibacterial” when discussing medications with patients. E.g., I suggest saying “You have a cold (a virus) so I don’t think you should take antibacterials“ instead of “You have a cold (a virus) so I don’t think you should take antibiotics.” The latter sentence leaves open the hope (in the mind of a typical patient) that antibiotics might also treat some viral infections. Using “antibacterial” is one more syllable than “antibiotic” but applying this linguistic lever could save doctors a lot of grief and dramatically reduce overprescription.

I’m not, of course, suggesting that academics and doctors need to ban the word entirely. “Antibiotic” can still be used in journals, presentations, and hallway conversations. My suggestion above is how to communicate with the public. That said, some scientists do in fact already use “antibacterial resistance” in journals and lectures in order to avoid ambiguity, so the change would not be a shock to anyone. And even Alexander Fleming used “antibacterial” 19 times in his 1929 paper on the isolation of penicillin. I.e., antibacterial is not a new word. You can even play it on Scrabble.

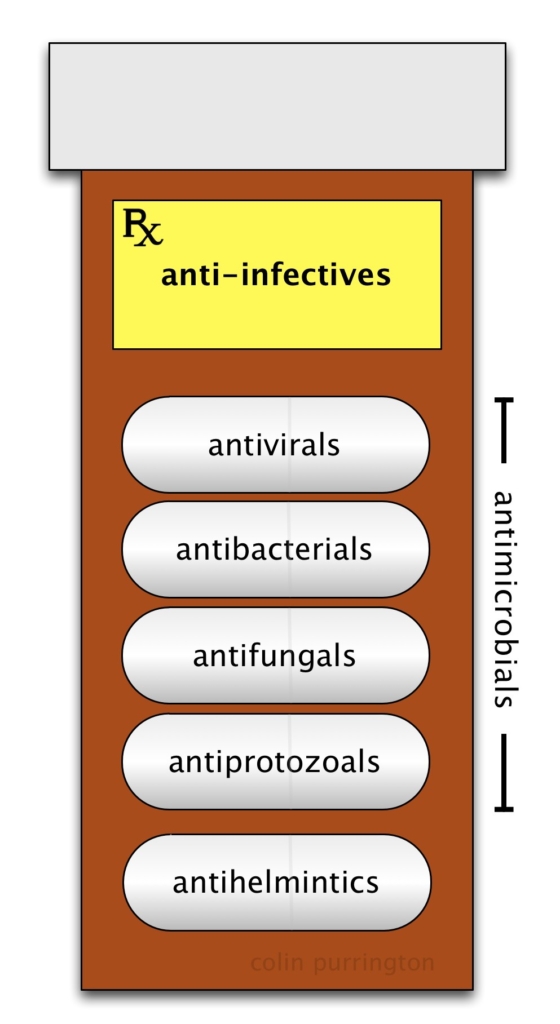

4. Hold an “Antimicrobial Awareness Week” instead

I think one major reason why antibiotic-awareness programs have so many cringe-worthy errors is that organizers are, ultimately, trying to alert the public to the dangers of evolution of resistance in all types of microorganisms, not just bacteria. So I think it is better to just have a more inclusive Antimicrobial Awareness Week. Then you can also talk about the evolution of resistance to antivirals, antifungals, antiprotozoals, and antihelmintics — nobody is left out.

On this note, I have found two organizations that have used “antimicrobial” in their awareness-week names: Misr International University, International Federation of Medical Students Associations. I will add others as I find them. The point is that for current organizers of Antibiotic Awareness Resistance Week, there are precedents for changing the name. And using search/replace can probably do the bulk of the change in just an afternoon.

5. Avoid equating bacteria with “germ” or “microbe”

For some reason, designers of antibiotic-awareness initiatives love to use “germ” and “microbe” as a synonyms for bacteria. Doing so reinforces among the public the idea that antibiotic is a synonym for antimicrobial. It’s fine, of course, to say that bacteria are a kind of microbe.

Plea to pollsters

I would be grateful if somebody could explore whether participants’ responses change when “antibiotic” is replaced with “antibacterial” in a survey question.

For example, ask, “How effective are antibacterials for treating viral infections?” I hypothesize that a person is more likely to a give a correct answer when “antibacterial” is used. This might seem obvious (because the word gives away the answer), but there are many biologists and physicians who I’ve spoken to over the years who truly don’t see how the word “antibiotic” is flawed.

Given how many hundreds of thousands of people are killed yearly by antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria, poll data like this might get health officials and physicians to reevaluate their love of the word, “antibiotic.” Switching to “antibacterial” in outreach programs and in doctors’ offices might result in far less misuse of antibacterials and therefore slow the evolution of resistance to such drugs. A simple search-and-replace action (antibiotic → antibacterial) would take mere seconds and potentially save thousands of lives. Given that current campaigns seem to be ineffective, I think it’s worth a try.

More information

Bennett, J.W. 2015. What is an antibiotic? Pages 1-18 in Antibiotics: Current Innovations and Future Trends, edited by S. Sánchez and A.L. Demain. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, UK.

Zimmer, B. 2015. A cure for ‘Antibiotic’ confusion? Wall Street Journal, Nov 24. (paywalled)