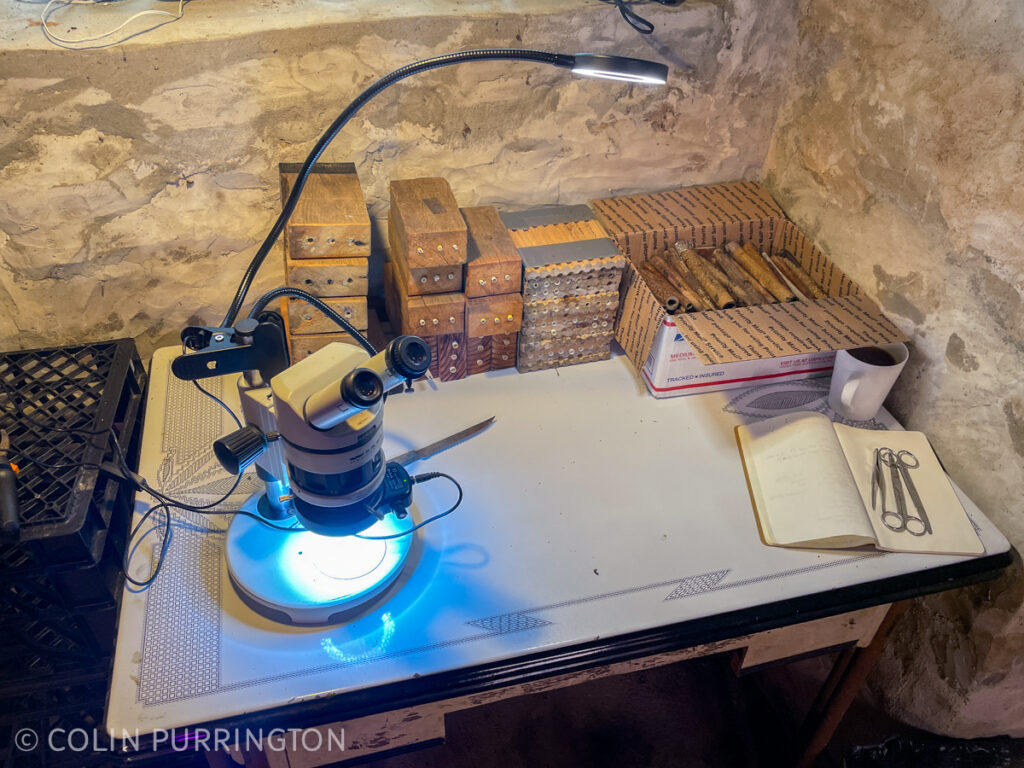

When the weather is cold and rainy in winter, I entertain myself by bringing the nests from my bee and wasp hotels inside for photo ops and cleaning. With a hot cup of tea (I’m in a cold basement), I carefully open up all the occupied nesting tunnels, then put the cocoons and larvae into vials so I can see who eventually hatches out in the spring. Here’s my set-up before I made a complete mess:

Removing the paper liners (here, straws from a local supermarket) from the nesting blocks is much easier with a pair of forceps. The blocks are necessary because if I just crammed paper straws into my bee hotel, every single nest would be parasitized by wasps that could easily get access to the larvae along the length of every straw.

Below are the cocoons of a mason bee, separated by mud plugs and covered with frass. They are probably Osmia cornifrons (pic of adult) or Osmia taurus (pic of adult), both introduced species that are frequent visitors at my hotels. Unwrapping the straws is usually pretty easy, but sometimes you need to use the forceps to grab onto the edges to complete the job.

I also had two stems filled with Georgia mason bees (Osmia georgica), a native species that has a beautiful blue body (pic of adult). It has smaller, bright orange frass and uses chewed plants to seal partitions. It also smells different.

Below is a visual reminder of why I need to sort through my nests each year: Houdini flies (Cacoxenus indagator). These kleptoparasitic dipterans eat the pollen balls that mason bees feed on, resulting in the death of the bee. So when I find them send them along to fly heaven. The common name is from their ability to bust open the mud plugs (they have inflatable heads for the job). Here’s a pic of an adult.

I also had grass-carrying wasps move into the observation panel, below, that I built a few years ago. There’s one nest near the top, and one at the very bottom, possibly provisioned by the same female. Because this panel slides in and out of the hotel easily, I was able to get a photographs of the adult, an egg, and a larva last year.

Here’s a close-up of the cocoon from the panel. It’s quite large. A photograph of a cleaned-up cocoon from a previous year is on my iNaturalist account if you want a better view. If you have a good eye, you might be able to make out a book louse (Liposcelis sp.) on the left-hand side of the cocoon. Here’s a close-up from a previous season if you’re curious.

One of my bee hotels is packed full of hollow stems, so for these I use a knife to split them open. Here’s a brood of potter wasps inside one of them. I’m not sure what species they are (or even genus) but I’ll know in several months when they hatch and I can get an identification on iNaturalist. And there’s a possibility that one or more of the larvae is harboring an internal parasite, too. Or at least that’s what happened in a previous year, when a beetle appeared (see my post about it). A beetle parasitizing one of my wasps was not on my Bingo card that year. I love surprises like that.

In the smaller stems I get lots of these cocoons, likely Trypoxylon collinum (pic of adult), a charming little wasp that feeds very small spiders to its young.

Although I enjoy looking through the nesting tubes, the main reason I do it is to make sure I’m not just breeding Houdini flies, pollen mites (pic), and pathogens that could easily spill out into bee and wasp populations near my house. I.e., if during my cleanings I felt that I was doing more harm than good to local native species, I’d shutter my hotels and find alternate entertainment.

As you may have noticed during the above, I love wasps. So if you have a bee hotel and get wasps, that’s a bonus, not a problem. And thus I implore everyone to not kill the larvae and the pupae simply because they are not mason bees. They both pollinate plants, plus wasps are fantastic at patrolling your vegetable gardens for pests, which they take back to their nests to feed to their young. If you’re on the fence about wasps, consider treating yourself to book on their biology and identification. I have Heather Holm’s fantastic Wasps: A Guide for Eastern North America. I’ve also heard great things about Eric Eaton’s Wasps: The Astonishing Diversity of a Misunderstood Insect and Seirian Sumner’s Endless Forms: The Secret World of Wasps.

More information

Below are my other posts about insect hotels if you want to learn more. If you have a question, send me an email via my Contact page.